Maharani Jindan-Queen Regent of the Punjab-noted the Sikh losses in the prior battles( Mudki, Ferozeshah, Aliwal) and despatched ten horsemen with an urgent message to the veteran general, Sham Singh Attariwala. He in turn, rounded up the support of immortals of the Khalsa-the Akali Nihangs-headed by Akali Hanuman Singh.

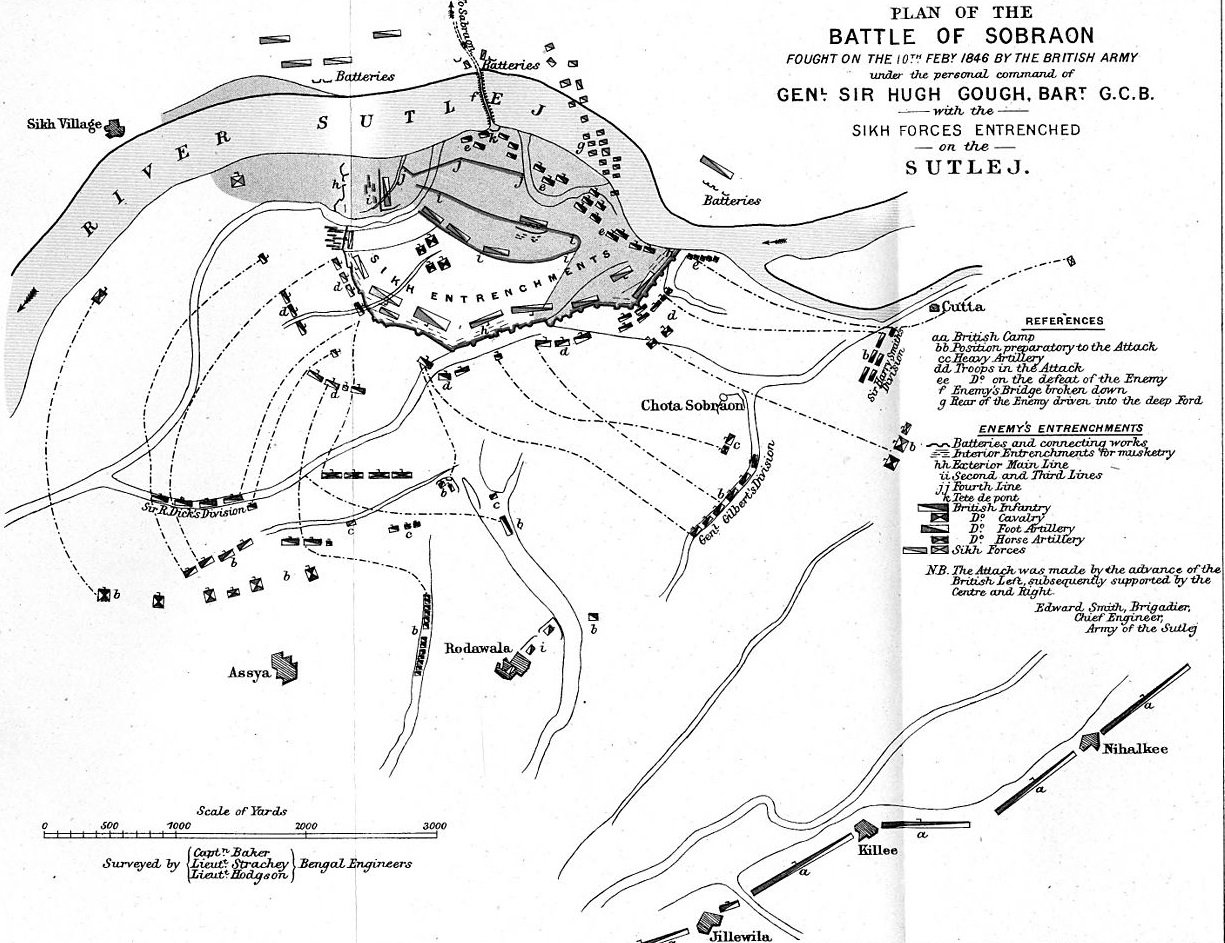

By the close of first week of February, 1846, the Sikh Army had constructed formidable entrenchments about two and a half miles long on the left bank of Sutlej near Sobraon. Their batteries were placed about six feet high protected by deep trenches. These defensive works were connected with the right bank with a bridge of boats. Some twenty to twenty five thousand men and seventy guns were placed behind these entrenchments. The weakest point in the Sikh line was its right flank where the loose sand made it impossible to build high parapets or place heavy guns there; it was to be protected by the ghorcharas and light camel guns which only fired balls one or two pounds in weight; moreover the command of this wing was reserved by Lal Singh for himself.

Sir Robert Dick’s Division was ordered to commence the attack on the right flank with Sir Walter Gilbert’s Division in immediate support on the right. Sir Harry Smith’s Division was to be close to Gilbert’s right to support him.

Dick’s Division advanced according to plan and found the defences on the right flank weak and easily surmountable. The 10th Queen’s Regiment broke through totally unopposed, but when the entire division had penetrated some way it was suddenly fallen upon by the Sikhs and driven back. Sir Robert Dick was himself mortally wounded. Now both Gilbert’s and Dick’s Divisions engaged in what may be called the deadliest hand-to-hand encounter with the Sikh infantry.

Robert S. Rait (1903). The Life and Campaigns of Hugh, First Viscount Gough, Field-Marshal.

For some time the issue of the Battle of Sobraon was hanging in the balance as the conflict raged fiercely. Cunningham, describing this contest, writes: “The round shot exploded umbrils or dashed heaps of sand into the air; the hollow shells cast their fatal contents fully before them and the devious rocket sprang aloft with fury to fall hissing amid a flood of men; but all was in vain, the Sikhs stood unappalled and flash for flash returned and fire for fire”. ‘The field was resplendent with embattled warriors. Then as Sir Herbert Edwards says, “The artillery galloped up and delivered their fire within 300 yards of the enemy’s batteries and infantry charged home with the bayonet and carried the works without firing a single shot. As it was the finest attack, so also did it meet with the most determined hand-to-hand resistance with which the Khalsa soldiers had yet opposed the British.” The tide of battle now turned against the gallant defenders and to make its turn irrevocable, the treacherous Commanders, Tej Singh and Lal Singh instead of leading fresh men to bolster up the defences, fled across the bridge of boats sinking the central boat after crossing.

Depiction of Sham Singh Attariwala, portrait kept at Ferozeshah Memorial

Gilbert’s Division led the third charge on the Sikh centre. Mounting on one another’s shoulders, the attackers gained a footing on the entrenchments and as they increased in number they rushed at the Sikh guns and captured them. Soon the news spread down the line that enemy troops had won their way through to Sikh positions. Sardar Sham Singh, seeing his army facing defeat, took the final fatal plunge. He spurred forward against the 50th Foot, brandishing his sword and calling on his men to follow him. But soon he fell from his horse, his body pierced with seven balls.

J.D. Cunningham, describes the scene, “The dangers which threatened the Sikh people pressed upon their mind and they saw no escape from foreign subjection. The grey headed chief, Sham Singh of Attari, made known his resolution to die in the first conflict with the enemies of his race and so to offer himself as a sacrifice of propitiation to the spirit of Gobind Singh ji and to the genius of his mystic Commonwealth”. ( History of the Sikhs).

As proof of this his dead body, according to the British Commander-in-Chief, ‘was sought for in the captured camp by his followers’, who were permitted to search for their dead leader. His body was discovered where the dead lay thickest. His servants placed the body on a raft and swam with it across the river.

The self-sacrifice of Sardar Sham Singh, the hero of Sobraon, had an inspiring effect. According to Cunningham, “No Sikh offered to submit and no disciple of Gobind asked for quarter. They everywhere showed a front to the victor and stalked slowly and sullenly away while many rushed singly forth to meet assured death by contending with a multitude.’ According to Lord Hardinge who was present in the battle, “Few escaped; none, it may be said, surrendered. The Sikhs met their fate with the resignation which distinguishes their race”.

According to Major Carmichael Smyth, “Tej Singh ordered up eight or ten guns and had them pointed at the bridge as if ready to beat it to pieces or to oppose the passage of the defeated army”. Many Sikhs died as the boats sank, EIC soldiers fired on the Sikhs in the river.

Again; “The Sikh troops, basely betrayed by their leaders who had come so it was said, and not without some appearance of truth……to a secret understanding with us, fought like heroes”, Smith, Life of Lord Lawrence, 1188.

Hesketh Pearson says, “A British defeat, was again turned into a victory by the convenient flight of Tej Singh who damaged the bridge of boats over the Sutlej on his way and so helped to drown a large number of his countrymen”.

Akali Hanuman Singh frescoe at Baba Atal, Amritsar

Akali Hanuman Singh who also fought in the battle lost many of the Akali forces in the hand to hand combat that took place. However whilst information is sparse Akali Hanuman Singh left the battlefield where he was hunted down to Patiala and eventually killed at Sohana (Chandigarh).

Sham Singh Attariwala, Gulab Singh Gupta, Hira Singh Topee, Kishan Singh (Son of Jemadar Singh Khusal Singh), Mubarak Ali, Shah Nawaz (son of Fateh Din of Kasur) all died in this battle which essentially finished off the older guard of Maharajah Ranjit’s Singh army.

Lord Gough paid great tribute to Sikh soldiers: “Policy precluded me from publicly recording my sentiments on the splendid gallantry of our fallen foe, or to record the acts of heroism displayed not only individually, but almost collectively, by the Sikh sirdars and the Punjab army: and I declare, were it not for deep conviction that my country’s good required the sacrifice, I would have wept to have witnessed the fearfully slaughter of so devoted a body of men”.

31st Foot under Sergeant Mcabe planted their recaptured standard in the mound, behind the fighting take place.

General Sir Joseph Thackwell who witnessed the battle wrote, “Though defeated and broken, they never ran, but fought to the last and I witnessed several acts of great bravery in their Sirdars and men”. Lord Hardinge, who saw the action, wrote: “Few escaped, none it may be said, surrendered. The Sikhs met their fate with the resignation which distinguishes their race”. This was a British victory against a people afflicted with internal treachery and treason and was the beginning of the end of the great Punjab Durbar.

The British Governor-General, Lord Hardinge, entered the Sikh capital-Lahore on 20 February 1846, and on 9 March imposed upon the young Maharaja Duleep Singh, then aged seven and a half years, a treaty of peace. Additional articles supplementary to the treaty, were added two days later on the 11 March 1846.

Key facts:

Unlike other battles of the Anglo Sikh Wars, the battle of Sobroan and the role played by Sham Singh Attariwala is celebrated in the Punjab and in wider parts of India.

Akali Hanuman Singh’s narrative is very interesting and deserves further attention. He was hounded and pursued through Patiala and Chnadigrah.

Many British regiments celebrate the battle of Sobroan as Sobroan day.

A fragment of the Colour carried by Sergeant McCabe is enclosed in a unique piece of silver, which is known as The Huntingdonshire Salt and is held by the 2nd Battalion. This is used for the ‘salt ceremony’, when newly joined members of the Battalion are invited ‘to take salt with the Regiment’.